INCOME, EQUALITY AND EQUITY

Income is a flow of factor incomes to households such as wages and earnings from work; rent from the ownership of land and interest & dividends from savings and the ownership of shares. Higher current income can lead to greater future income through the aquisition of wealth generating assets as shown in the consumption possibility frontier.

Wealth is a stock of financial and real assets such as property, savings in bank and building society accounts, ownership of land and rights to private pensions, equities, bonds etc...

Absolute poverty

Absolute poverty measures the number of households unable to afford what are agreed to be basic or essential goods and services. There is always a degree of subjectivity in deciding which goods and services should be included in a definition of a basic standard of living. The concept of absolute poverty for people living in New Zealand is clearly different for poor households in less economically developed countries.

Relative poverty measures the extent to which a household’s financial resources falls below an average income level. There is little doubt that New Zealand has become a more unequal society over the last 25 years reflected in a persistently high level of relative poverty.

The poverty line is currently measured at 60 per cent of median income level – where the median is the

level of income after direct taxes and benefits, adjusted for household size, such that half the population is above the level and half below it. This definition is a standard that changes as median income levels change; it is a measure of relative poverty.

There are numerous explanations both for the existence and persistence of a huge divide in incomes and wealth within NZ. Most of them are directly economic in origin, but some are linked to social change.

A summary is provided below:

Differences in pay in different jobs and industries

Industries where there is a lot of growth and a shortage of skilled workers will see an increase in incomes, while industries which are declining or where the jobs do not require a lot of skill ( and so workers are easily replaced) will see low wages.

The lowest paid jobs tend to be in the service industires and with the decline in union membership, these wages have tended not to rise recently.

Income inequality tends to rise during periods of rapid wage growth because the poorest households are the most likely to contain non-working individuals. And because wages will rise most quickly for those workers with skills that are in high demand.

State welfare benefits normally rise in line with prices (they are index-linked) rather than with earnings. Therefore, households dependent on welfare assistance see their relative incomes fall over time. This is a particular problem for many thousands of pensioner household.

Unemployment is a key cause of relative poverty (i.e. an increase in income inequality). For example, a serious problem is the increase in the number of households where no one is in paid employment and where a family is dependent on state welfare aid.

Changes to direct and indirect taxes have contributed to an increase in relative poverty. Income tax rates have fallen over the last two decades. The top marginal rate of tax fell from 69% in 1981 to 33% in 1986 where it has remained. These tax reductions allow people in work to keep a higher proportion of their earned income. The benefits from lower taxes have flowed disproportionately to people on above-average incomes because of a fall in the progressive nature of the NZ’s direct tax system.

There has been a switch towards indirect taxes since the 1980’s including higher rates of GST and higher excise duties on petrol, alcohol and cigarettes. Some of these indirect taxes have a regressive effect on the distribution of income.

The Impact of Current Income on Future Income

Consumption Possibilities Frontier

The model shows the link between income and wealth, when a consumer earns enough income they can save their surplus income and invest in income-generating financial assets such as term deposits, shares, gold, and rental property. This highlights the gap between people who have a higher income or are able to spend less, and so are able to create wealth, and those who either have to spend all their limited income or choose to spend it all. The people in a position to generate long-term wealth, will have a higher future income and so expand their future consumption possibilities by increasing their income through income-generating assets - such as interest from saving and income from rents from property.

.

.

The Impact of Income and Wealth

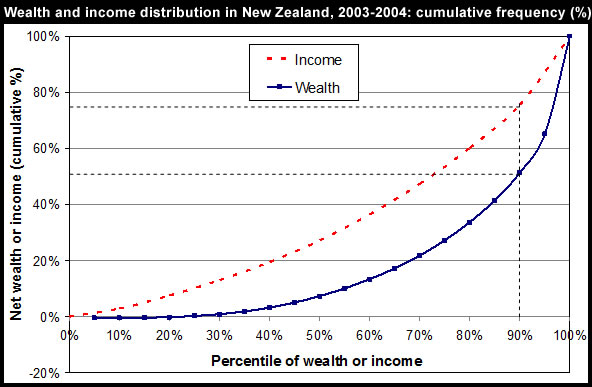

The diagram below shows that incomes are more equal in New Zealand than the distribution of wealth.

There may be a number of reasons for this.

- The impact of those on a higher incomes being able to save more and so greater wealth/ asset accumulation.

- The impact of inheritance on wealth accumulation for some families.

- Middle income families may have enough to live comfortably, but not enough to save.

- The choices people make about consumption and saving.

Those in the bottom 50% of households in the economy only have 6% of the countries accumulated wealth.

The top 10% of households have 50% of the countries accumulated wealth.