| What is Inflation? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What is inflation? Inflation is defined as an increase in the general level of prices over a period of time. It is measured by a percentage increase in the Consumers Price Index (CPI). This means that a person will not be able to buy as much as they were able to before. Inflation reduces the purchasing power of money. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Increases in relative prices and the general price level | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The market for different products is always changing as demand and supply conditions change. A change in demand or supply conditions for a range of products will cause a change in the general price level. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| If

Aggregate Demand increases ( shifts right) due to an increase in - Consumption. - Government spending. - Investment. - Net Exports. - Income. then there will be a shift of the Aggregate demand curve to the right and this will cause inflation. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| If Aggregate Supply

decreases due to a change in supply conditions such as - In an increase in general production costs. - Changes in productivity. - Changes in the price of imports (raw materials). - An imposition of an indirect tax such as G.S.T. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Just because some prices are rising, does not necessarily mean that there is inflation. These are relative price rises. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Define Inflation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name some factors that could lead to an increase in aggregate demand (a shift of the aggregate demand curve to the right). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name some factors that could lead to an increase in aggregate supply (a shift of the supply curve to the left). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A general increase in the price level. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is only when the average price is rising or

falling that we use the terms inflation or deflation. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Inflation occurs when you need more money to buy the same basket of goods that you would normally buy. The value of your money has fallen because you now have to use more of it to buy the same amount of goods. The value of your money has decreased as it buys less than before. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Inflation -a general increase in the average price level. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deflation - a general decrease in the average price level. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disinflation - the rate of inflation falls. The average price level is increasing but at a lesser / slower rate than before. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

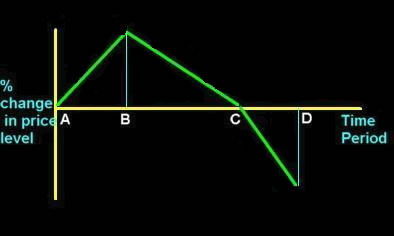

| USE THE GRAPH BELOW TO ANSWER THE QUESTIONS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What type of inflation occurs from periods A - B? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What type of inflation occurs from periods B -C? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What type of inflation occurs from periods C - D? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nominal numbers are before adjusting for inflation. They're the numbers we usually use, for everyday purposes, when we talk about prices, growth and so on. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CALCULATING THE EFFECT OF INFLATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| We can calculate the effect of inflation on

the price of a good or service by multiplying the original price of the

good x 1. the rate of inflation as a decimal. E.g. if the rate of inflation was 5% and the price of the good $11 then the effect of inflation on the good in the first year would be 11 x 1.05 = $11.55 The effect of inflation on prices over time can be shown in the following table

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Worst Episode of Hyperinflation in History: Yugoslavia 1993-94 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Under Tito Yugoslavia ran

a budget deficit that was financed by printing money. This led to rate of

inflation of 15 to 25 percent inflation per year. After Tito the Communist

Party pursued progressively more irrational economic policies. These

irrational policies and the breakup of Yugoslavia (Yugoslavia now consists

of only Serbia and Montenegro) led to heavier reliance upon printing or

otherwise creating money to finance the operation of the government and the

socialist economy. This created the hyperinflation. By the early 1990s the government used up all of its own hard currency reserves and proceeded to loot the hard currency savings of private citizens. It did this by imposing more and more difficult restrictions on private citizens access to their hard currency savings in government banks. The government operated a network of stores at which goods were supposed to be available at artificially low prices. In practice these stores seldom had anything to sell and goods were only available at free markets where the prices were far above the official prices that goods were supposed to sell at in government stores. Delivery trucks, ambulances, fire trucks and garbage trucks were also short of fuel. The government announced that gasoline would not be sold to farmers for fall harvests and planting. Despite the government desperate printing of money it still did not have the funds to keep the infrastructure in operation. Pot holes developed in the streets, elevators stopped functioning, and construction projects were closed down. The unemployment rate exceeded 30 percent. The government tried to counter the inflation by imposing price controls. But when inflation continued the government price controls made the price producers were getting ridiculously low they stopped producing. In October of 1993 the bakers stopped making bread and Belgrade was without bread for a week. The slaughter houses refused to sell meat to the state stores and this meant meat became unavailable for many sectors of the population. Other stores closed down for inventory rather than sell their goods at the government mandated prices. When farmers refused to sell to the government at the artificially low prices the government dictated, government irrationally used hard currency to buy food from foreign sources rather than remove the price controls. The Ministry of Agriculture also risked creating a famine by selling farmers only 30 percent of the fuel they needed for planting and harvesting. In October of 1993 they created a new currency unit. One new dinar was worth one million of the old dinars. In effect, the government simply removed six zeroes from the paper money. This of course did not stop the inflation and between October 1, 1993 and January 24, 1995 prices increased by 5 quadrillion percent. This number is a 5 with 15 zeroes after it. The social structure began to collapse. Thieves robbed hospitals and clinics of scarce pharmaceuticals and then sold them in front of the same places they robbed. The railway workers went on strike and closed down Yugoslavia's rail system. In a large psychiatric hospital 87 patients died in November of 1994. The hospital had no heat, there was no food or medicine and the patients were wandering around naked. The government set the level of pensions. The pensions were to be paid at the post office but the government did not give the post offices enough funds to pay these pensions. The pensioners lined up in long lines outside the post office. When the post office ran out of state funds to pay the pensions the employees would pay the next pensioner in line whatever money they received when someone came in to mail a letter or package. With inflation being what it was the value of the pension would decrease drastically if the pensioners went home and came back the next day. So they waited in line knowing that the value of their pension payment was decreasing with each minute they had to wait in line. Many Yugoslavian businesses refused to take the Yugoslavian currency at all and the German Deutsche Mark effectively became the currency of Yugoslavia. But government organizations, government employees and pensioners still got paid in Yugoslavian dinars so there was still an active exchange in dinars. On November 12, 1993 the exchange rate was 1 DM = 1 million new dinars. By November 23 the exchange rate was 1 DM = 6.5 million new dinars and at the end of November it was 1 DM = 37 million new dinars. At the beginning of December the bus workers went on strike because their pay for two weeks was equivalent to only 4 DM when it cost a family of four 230 DM per month to live. By December 11th the exchange rate was 1 DM = 800 million and on December 15th it was 1 DM = 3.7 billion new dinars. The average daily rate of inflation was nearly 100 percent. When farmers selling in the free markets refused to sell food for Yugoslavian dinars the government closed down the free markets. On December 29 the exchange rate was 1 DM = 950 billion new dinars. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| At the end of December the

exchange rate was 1 DM = 3 trillion dinars and on January 4, 1994 it was 1

DM = 6 trillion dinars. On January 6th the government declared that the

German Deutsche was an official currency of Yugoslavia. About this time the

government announced a new new Dinar which was equal to 1 billion of the old

new dinars. This meant that the exchange rate was 1 DM = 6,000 new new

Dinars. By January 11 the exchange rate had reached a level of 1 DM = 80,000

new new Dinars. On January 13th the rate was 1 DM = 700,000 new new Dinars

and six days later it was 1 DM = 10 million new new Dinars. The telephone bills for the government operated phone system were collected by the postmen. People postponed paying these bills as much as possible and inflation reduced there real value to next to nothing. One postman found that after trying to collect on 780 phone bills he got nothing so the next day he stayed home and paid all of the phone bills himself for the equivalent of a few American pennies. Here is another illustration of the irrationality of the government's policies. James Lyon, a journalist, made twenty hours of international telephone calls from Belgrade in December of 1993. The bill for these calls was 1000 new new dinars and it arrived on January 11th. At the exchange rate for January 11th of 1 DM = 150,000 dinars it would have cost less than one German pfennig to pay the bill. But the bill was not due until January 17th and by that time the exchange rate reached 1 DM = 30 million dinars. Yet the free market value of those twenty hours of international telephone calls was about $5,000. So the government despite being strapped for hard currency gave James Lyon $5,000 worth of phone calls essentially for nothing. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||